Airlines in Transition - A rust belt industry in need of revenues

The world of data has changed radically in the past decade. Facebook has altered the way people communicate, simultaneously delivering a mountain of data to its owners; Google and Apple are rapidly building the biggest data factories ever assembled; Amazon knows all about our reading and consumer habits and is expert at exploiting them; and a host of online travel agents and others are taking advantage of their youthful IT profiles to accumulate data mines that are potentially worth tens of billions of dollars.

Meanwhile most airline managements are, delinquently - for there can be no other word for a vividly available resource which is being so clearly squandered - sitting idly by while the host of data they accumulate (or waste) simply runs like water through the sand.

This report is extracted from the August-September 2012 issue of CAPA's Airline Leader hard copy journal. Click here to view a cutting edge html5 version.

- Legacy airlines are not effectively utilizing the vast amount of data they have on their customers, missing out on potential revenue opportunities.

- The failure to exploit data is due to a combination of silo thinking, outdated technology, and a focus on traditional business models.

- The rise of data mining companies poses a threat to airlines, as they have better access to customer data and are more adept at monetizing it.

- Airlines are constrained by privacy regulations and cross-border data transfer limitations, while data mining companies operate in a more flexible and less regulated environment.

- The airline industry is facing multiple challenges, including rising fuel prices, increased competition from low-cost carriers, and external threats such as pandemics and climate change.

- Airlines need to reinvent themselves and prioritize data management to stay competitive and avoid being disenfranchised by data mining companies.

How aviation has become a rust belt industry...while dumbly sitting on a goldmine of unused data: Part 1

By definition anyone who flies on a commercial airline is among the world's top 10% most affluent people. This distinguished group has discretionary money to spend and has demonstrated a will to do so by getting on a flight. The Top 10% are patently the world's best marketing targets. And airlines know all of them; very intimate data are available to be mined.

Yet, through a combination of silo thinking and antique technology, legacy airlines are looking in the other direction, still entirely focused on what is repeatedly described as "an unsustainable business model", buying large amounts of expensive boys' toys, constantly in conflict with their legacy unions, regulators, suppliers and airports, burning billions of dollars of fuel - and drastically underperforming financially.

The proposition of this report is simple: until now, this profligacy with data has not mattered, except in wasting valuable potential resources. But now, unless airlines wake up to the vast goldmine they are overlooking, the pace of change in data mining guarantees that one or more of the large miners (current or future) will intervene to grab these riches.

In the process, and almost as a by-product, the miners will take control of the space between airlines and their customers, with all the ramifications that implies. That would spell the end of airlines as we know them. Most would become mere transportation tools, contracted to carry commercial "cargo" - just as telecoms and rail operators have become regulated "pipes" or "tracks", to be rented to entrepreneurial companies.

The purpose of this report is consequently to highlight how the legacy airlines' inward thinking is causing them to overlook the goldmine of retail opportunities that now presents itself. This goldmine is commonly called "Big Data".

Unless airlines wake up to the vast goldmine they are overlooking, the pace of change in data mining guarantees that one or more of the large miners (current or future) will intervene to grab these riches.

Big Data is more than an IT geeks' concept. Last year, as a global explosion of investment in database software, servers, storage systems and other hardware (not the least security-related) occurred, data centre hardware expenditure grew to USD100 billion, according to venture capitalists Kleiner Perkins Caulfield and Byers. With tens of millions of innovators across the IT University of the World, the potential for mighty change in this area is unquantifiable. Meanwhile, most airlines continue on track, blissfully unaware of the goldmine beneath them, or of the threat around the corner.

Big Data meets small strategy

The reasons for the airlines' data delinquency are not simply shortcomings in IT sophistication - despite the often ageing and disparate systems that typify legacy airlines' information silos.

The problems are much deeper-rooted, deriving from a history focused on buying and flying metal. The big boys' toys condition is fading - but many of the legacies overhang thinking and strategy.

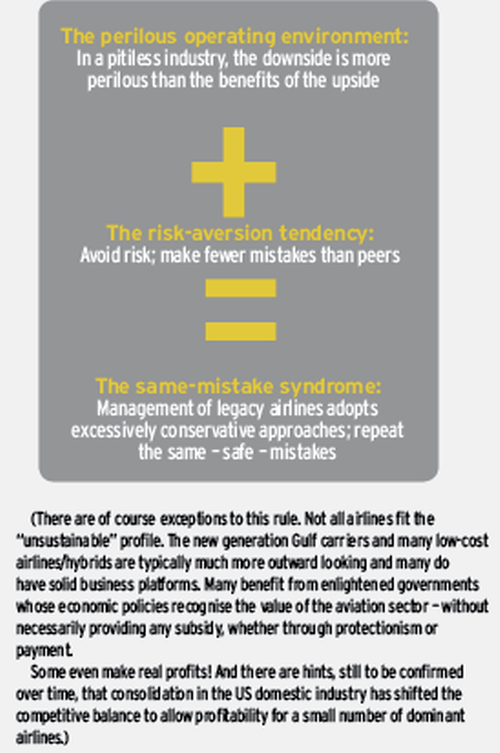

Often this is a derivative of the very incestuousness of the airline business. Airlines are remarkably inward looking companies, with a strong preference for internal appointments. For example, and to the constant frustration of analysts and head-hunters, most managements typically persist in benchmarking against other airlines. Where these too are part of the same "unsustainable" industry this can only be a recipe for mediocrity, complete with ingrained financial shortcomings.

Why would anyone intentionally measure performance against companies renowned for their inadequacy? Because it makes life easier? Whatever the reason, it is unlikely to stimulate new age thinking. In the process it helps entrench a mindset that is more focused on defensiveness and risk mitigation than innovation.

This credo says it is better to be safely less bad than your competitors than to take risks to try to outpace them.

A result of perpetuating peer airline thinking is that the likelihood of radical innovation, for example, spending USD100 million on understanding and overhauling an aged data strategy because of its future potential value, is as remote as Tristan da Cunha.

Yet to invest 50 times that much on buying big machines that generate at-best marginal returns is a breeze. It's easier because all the legacy systems (and professionals) are in place to help analyse operating economics, comply with regulations, plan networks to fly them on, and judge likely future market trends and competitor actions; a third of most airlines is in its operations division. That is a difficult million tonne tanker to turn around. Meanwhile, cutting back on "IT spend" is also a breeze.

The combination of these industry features - incestuousness; entrenched operating dynamics; weak strategic thinking around new opportunities; and the awareness that the next setback can occur out of the blue from any direction - all lead to a high level of management risk aversion.

A result of perpetuating peer airline thinking is that the likelihood of radical innovation - for example, spending USD100 million on understanding and overhauling an aged data strategy because of its future potential value - is as remote as Tristan da Cunha.

The ingredients of a rust belt industry

Thomas Hobbes distilled the nature of the airline industry in his 17th century work, the Leviathan: "Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

The rust belt airline industry: "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short"

Hobbes was in fact describing the state of mankind. The only difference: the airlines' temporal existence. Indeed, most problems of legacy airlines come from the fact that their lives are not short. The longer they live, the heavier the baggage of their inheritance. Creative destruction is not part of their agenda either.

This is what makes it so important that they at least reinvent themselves to embrace the value of data - while they are still able to negotiate from a position of relative strength.

Meanwhile, the description "unsustainable" remains synonymous with the industry.

But alarmingly, there is no clear signal that anything is going to get better - without completely reinventing the legacy model.

The legacy airline management equation

To make this outlook worse, several industry-altering events will occur by the end of this decade. An already "unsustainable" airline model will only get worse.

Whatever the exact timing of these seminal events, there is consensus that each will materialise some time before 2020. They are unlikely to be synchronised; some have short-term probabilities and others will unfold over time. They are mostly threats.

Fuel is the ever-present most obvious threat - its supply and its pricing. The airline industry must rely on oil for the bulk of its propulsion needs for the foreseeable future; there is simply no viable alternative in sight. The airlines' biggest single expense, some 40% of costs, is outside management control, on this uncontrollable and volatile product.

Moreover, the industry has been built around fuel prices that most comfortably sit below USD100 per barrel. Higher prices can be absorbed, but as the price increases, so the reliance on higher yields to sustain the industry must grow - thereby changing the variety of airline profiles which currently exists.

Almost every forecast envisages fuel prices above USD200 a barrel by 2020. The number of supporters of "peak oil" has perhaps peaked as new resources emerge, but relentless price increases, accompanied by occasional spikes, account for the majority vision. A sustained aviation fuel price above USD150 a barrel will inevitably influence the nature and shape of airline models; when that figure approaches USD200, very substantial change will be unavoidable.

Worse, it is the intensity of the price spikes that is most threatening to airline well being. The inability to adjust to sudden large price variations creates greater challenges than steady rises - even if the latter turn out to be like the boiling frog. In 2008 as fuel prices rocketed up, many airlines were hastily re-examining their viability.

Fortunately the 2008 spike was relatively short and, surprisingly, mostly accompanied by strong consumer demand, able to absorb a flurry of fuel surcharges. It was then quickly followed by a breathtaking slump to below USD50, providing room for financial recovery as demand slackened and discounted fares were necessary.

In retrospect 2007/08 was a relatively benign fuel price crisis. Had the variables emerged differently the damage would have been much greater. But the price spike did show that a lot of airlines were able to hold their breath for about six months without being overcome by oxygen starvation.

The crisis also suggested that the impact on reserves and immediate profitability was such that a longer-lasting spike, with different peripheral effects, could have been terminal for more than a few companies. Thus, whatever the long-term trend, every airline's survival risk management strategy must now incorporate a reckoning of a more malignant scenario of price spike than occurred in 2008.

Tony Tyler, IATA CEO, summed up much of the industry status recently:

"Between 2002 and 2011 aggregate airline revenues totalled $4.6 trillion. And we lost $16 billion. Our best annual net profit margin of this century was just 2.9%. A business that cannot generate a satisfactory return on capital is not sustainable over the long term and that is the position in which the air transport industry finds itself.

"I've described the natural state of the airline industry as being in crisis, interrupted by brief moments of calm. Nothing I have seen since taking up my current job has caused me to change that view. We are in a moment of relative calm, although quite possibly it is only the lull before the storm. The industry is fragile." (SITA Air Transport IT Summit, Brussels, Jun-2012)

IATA net profit: 1997 to 2012F

IATA operating profit: 1997 to 2012F

Briefly, the industry made money in 2010.

Even if fuel prices fall in the short term, as they did after the GFC, the long term will be unforgiving.

Most airlines have since adjusted their fuel hedging strategies as part of this enforced risk management reassessment, in a bid to soften the effects of future spikes. Hedging is however expensive, can bring its own risks (such as sometimes very costly mark-to-market adjustments) and is only ever a temporary and limited solution. No airline hedges all of its needs, relying on the practice to guarantee a level of predictability in planning for a year or so ahead.

Alternative fuels cannot offer a solution in the medium term and present large cost challenges. Environmental issues will increasingly conspire against airlines. Aside from governments taxing airlines as a simple source of revenue - some more rapaciously than others - the incremental effect of environmental demands will progressively force fuel costs up. Together with taxes, the added cost of alternative fuel production and its physical distribution will inevitably create additional cost burdens.

Fuel prices and spikes are just one constant danger; there are also the regular external threats inherent in the "constant shock syndrome"

- all of them are beyond the control of airline management. Recent shocks have included:

In the 15 years since the Asian financial crisis of 1997, there has not been a period of more than two years without one or more of "external threats" impacting seriously on the airline industry. It would be brave, if not foolish, to assume a greatly different profile for the future. The greatest threat is of pandemic - which the World Health Organisation has said "is not a matter of whether, but when".

SARS drove Cathay Pacific to within days of grounding its entire fleet in 2003. Such a threat has the power to change the industry irreversibly. While the same can be said of climate change effects, the great difference is that the impact of pandemic allows no time for adjustment.

More difficult to understand is how and why airline managements blindly persist in what is effectively a public service function, providing a platform for other industries to generate profits.

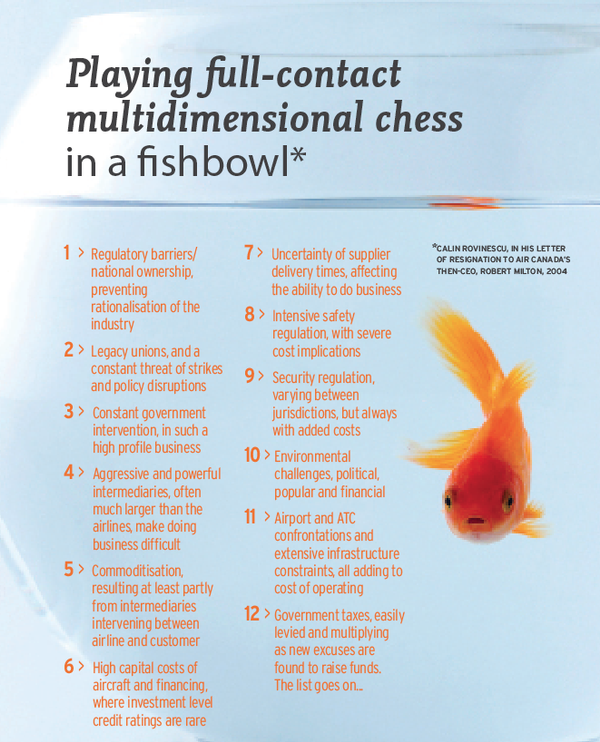

But it is the day-to-day grind that diverts management attention from the real opportunities. Aside from these life threatening conditions, there is a forbidding daily round of challenges to pre-occupy managements and boards.

It is small wonder that long-established airline companies have little time to concentrate on seeking new ways of making money; they are far too busy surviving the myriad affairs that afflict them, fighting with governments, financiers, suppliers, intermediaries, airports and wrestling with internal legacy disputes.

Faced with such a forbidding list of day-to-day challenges it is almost excusable that the industry consistently fails to return even its cost of capital.

The real issue is that the world has changed, inside and outside the industry.

But more difficult to understand is how and why airline managements blindly persist in what is effectively a public service function, providing a platform for other industries to generate profits. The answer is partly linked to the "glamour" and high profile of aviation (although in the mature markets, these have become tarnished qualities); also to the mere fact that the company exists, supported in its role by a large array of invisible inertial forces, ranging from regulation and nationalism to sheer protectionism.

For those companies which are publicly listed, equity sources are, however, becoming scarcer. The only thing that keeps many airlines flying is their continuing ability to raise and (usually) repay debt. Part of the larger problem is that some airlines are government supported. There are many nuances to this (including the very substantial "subsidy" value of protecting a listed flag carrier) and, in reality, it is only one small ingredient among the much more fundamental issues facing legacy airlines. The real issue is that the world has changed, inside and outside the industry.

Within the airline industry massive challenges have arisen for legacy airlines on both short-haul and long-haul operations

Here the European network airlines are most at risk, confronted by economic stagnation and the prospect of low growth at home. The major European network carriers - with an average age of well over 60 years - have seen their short-haul routes damaged greatly at the hands of LCCs.

LCCs have been eroding the ability to compete on intra-European routes, causing the full service airlines to cut back on frequency (thus reducing the quality of network connections) and to lose money carrying point to point traffic in direct competition with the lower-cost operators. Air France has publicly disclosed that, despite several years of cost reduction measures, its unit costs on short-haul operations are at least 20% - and probably considerably more - above airlines such as easyJet.

The power of loyalty programmes and connections into long-haul services offer a partial buffer against this disadvantage, allowing some yield premium. But the bulk of short-haul traffic is still point to point and so must compete head to head with LCC pricing.

To reduce costs by 30% in a legacy airline - or any legacy company for that matter - is near-impossible without serious loss of quality and a negative brand impact. At the same time, the prospect of achieving and maintaining significant increases in yield seems more and more remote.

In Asia, where union forces are often less resistant to change, most full service airlines have adopted the simple approach of establishing a stand-alone low-cost subsidiary. This permits the advantages of greenfield establishment, free of legacy costs and, where there is a sound model, the ability to connect into the parent without loss of the original brand integrity.

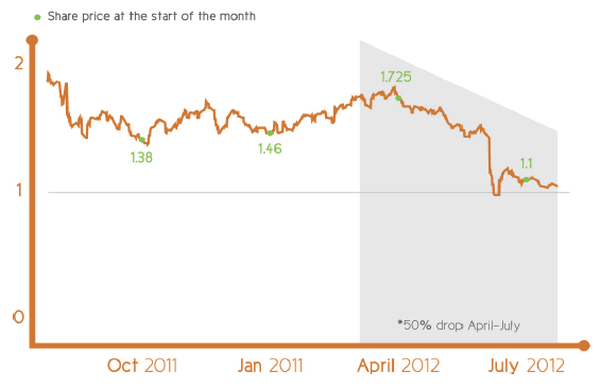

Not a pretty trend...

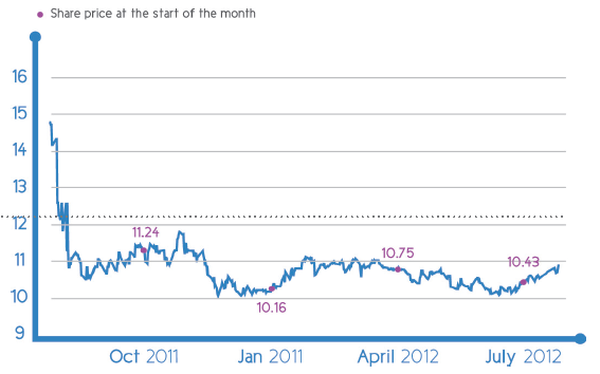

Qantas stock price (in AUD): Oct-2011 to Jul-2012

Air Canada stock price (in CAD): Oct-2011 to Jul-2012

Singapore Airlines stock price (in SGD): Oct-2011 to Jul-2012

Air France stock price (in EUR): Oct-211 to Jul-2012

Not all of the Asian offshoot models have got it right. In such a turbulent and ebullient growth environment, experimentation is most appropriate, complete with inevitable mistakes.

But Asia has the advantage that in many cases the rate of market growth in this leisure sector will deliver success where elsewhere in the world it may fail. One model that offers a design for others is clearly Qantas' Jetstar. This was the first of the existing crop of subsidiaries now in operation and has been much more strategically thought out than many others (see Airline Leader Issue 8).

The logic of a standalone partner is not always so easily implemented however. Where the inertial forces of powerful pilots' unions restrict strategic options, as they do in Europe, the answer to this competitive dilemma is much more complex. Lufthansa has taken baby steps in substituting its lower-cost airline acquisitions for the higher-cost mainline airline, most recently reshaping loss making Austrian to use its regional profile, Tyrolean.

Air France has also gently tried to decentralise its pilot base away from Paris and more recently to rely more heavily on Transavia, the jointly held AF-KLM lower-cost operator; and IAG is pushing through the use of lower-cost Iberia Express, along with part owned Vueling, to provide intra-European services.

All of these, however, are half measures and greatly constrained by the constant threat of pilot backlash if the moves are too rapid. Thus, for example an Air France move to reduce costs by 20% over three years relies on being able to survive during that period while levels remain well above the competition (as well as assuming the others will not outpace AF's reductions).

To reduce costs by 30% in a legacy airline - or any legacy company for that matter - is near-impossible without serious loss of quality and a negative brand impact.

The smaller network airlines, such as Finnair, SAS and some other flag carriers in Eastern Europe, are also being squeezed and are responding by cost- and route-cutting (and some others - but not many - like Malev, prevented by EU rules from government bailout, bmi and Spanair, have disappeared). The umbrella of global alliances provides some protection, especially for the larger carriers, but costs are costs.

On long-haul routes, the pressures are intensifying too. Until the Gulf carriers gained the bulk they possess today, it was reasonably predictable that the major network carriers - at least - could recoup short-haul losses by exercising their long-haul market power, singly and through alliances. But these services too are now coming under serious attack, as Emirates, Etihad and Qatar often offer a more convenient and lower priced service, usually with higher product quality and supported by intelligent national strategies. The older legacy network models are coming under attack from all quarters.

So what is about to happen now is not just another incremental issue that can be addressed with mere step changes. As Nawal Taneja says in this edition of Airline Leader, it must be tackled "at the transformative, not incremental, end of the spectrum".

Without re-invention the worst is yet to come. The greatest emerging threat is much less visible and at the same time much harder to guard against. And it comes from developments well outside the airline industry.

It is the risk of being totally disenfranchised.

Beware, the Data Miners are coming!

There are any number of emerging companies whose stock in trade is accumulating and monetising personal data. And data about airline passengers is becoming more and more accessible - and more valuable by the day.

...and it's GOLD they're mining

Legacy airlines have for decades had access to intimate data on hundreds of millions - in fact billions! - of travellers. But in most cases they have been criminally careless of the riches buried deep in their databases - or more frequently, simply discarded. When it comes to data usage (and nobody, but nobody, has access to more potentially valuable data than the airlines), incremental change is patently useless. Yet there would be few airlines who see this as a resource to focus on.

As a recent report from the Economist Intelligence Unit spelled out: "Because the shifts in both the amount and potential of today's data are so epic, businesses require more than simple, incremental advances in the way they manage information. Strategically, operationally and culturally, companies need to reconsider their entire approach to data management, and make important decisions about which data they choose to use, and how they choose to use them."

When it comes to "reconsidering their entire approach to data management", airlines are well behind the eight ball. The information/activity silo problem is ever present. But this is hardly a new phenomenon. Management, analysts, essentially anyone who has ever studied the way an airline works, have seen this as an issue for decades. It's been a perpetual problem with a perpetual no-response.

Even where an airline has developed a powerful frequent flyer programme, the level of intelligent FFP data integration with other internal streams of data is limited by the complexity of matching across different and independent IT silos. And not even the more sophisticated FFPs are effectively exploiting the information captured in their own, usually newer system.

Take one very simple example: the PNRs ("passenger name record" that is allocated to every passenger). They tell who flies, how often they fly, where they fly, how rich they are, who they work for; there is almost no limit to the information which cannot be derived about a passenger, especially where a series of trips is analysed over a period of time.

A few years ago - in pre-Facebook days - a group of analysts picked up a discarded boarding pass left on a tube train in London. From the information on the pass, they were able to aggregate the airline data with other publicly available data sources, leading to complete discovery of the traveller's full residential details, how much his mortgage was, where he worked and his salary, where his children went to school and how old they were - essentially anything that would be of value in developing a selling profile. That's not to suggest airlines should be probing that far into their customers' lives, but it does give an example of the scope of intelligence which is going begging.

Derived from individual passenger reservations, the data from PNRs is however scarcely used for any value-generating purpose. Most frequently the PNRs are simply dumped after a couple of days. Commonly they simply reside with OTAs (supposedly an arch enemy in the distribution chain) to dispose of.

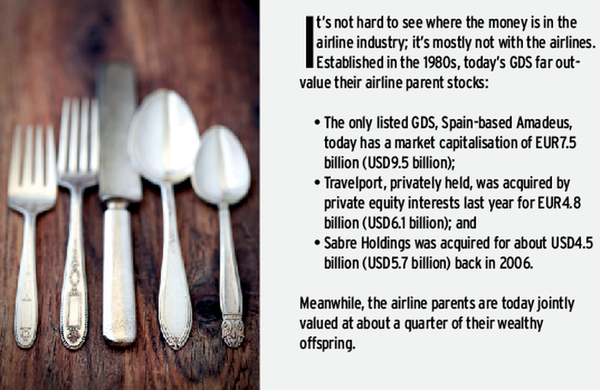

There is a track record here too, of the airlines giving away their inventory. By relinquishing control of immensely granular detail to independent computer reservations systems over the past two decades - even after competition authorities had sanitised the previously biased CRSs to allow their airline creators to own them - a major source of revenue was ceded to the newly empowered CRS/GDSs.

Ironically, the transfer of data (inventory) was mostly to help underpin the ailing finances of airline operations. As recently as Mar-2012, Air France-KLM sold 7.5%, of a total of 15.2%, of its holding in Amadeus for EUR467 (USD591 million). The strategy? To help restore profitability in its airline operations. In the previous "tough year", Air France-KLM made a net loss of EUR809 million (USD1.02 billion) flying passengers.

(Each of the other founders of Amadeus, the European counterpart to US airline CRSs, Iberia and Lufthansa have also sold down to about 7% shares in the company, having progressively liquidated to generate cash; SAS, also a founding member, has had to dig deeper into the kitty and no longer owns a share.)

To add insult to injury, a large part of the unit transaction fees paid so reluctantly by airlines to the GDSs is redistributed to travel agents, online and shopfront - entrenching what many airlines consider to be the commoditisation of their products and the market power of those intermediaries. One consequence of this, it is argued, is that the airlines are unable to generate maximum impact from ancillary revenues.

At the same time, this feeding chain (or business model) is so well entrenched that, for the time being at least, it is near-impossible for another party to intrude. Long-term deals are locked in with agents, commission payments are so lucrative that behavioural patterns are very difficult to disrupt and there are - for now - few companies with the ability or desire to break the cycle. There are many other more lucrative goals for the big IT-based firms to pursue than charging commission on airline ticket sales.

Selling off the family silver to prop up the rust belt operations

But add (big) data into that mix and the complexion could change very rapidly. Airlines may not be the most lucrative targets on the horizon - but their high net worth customers certainly are.

The growing risk of disenfranchisement

In this scenario, the risk of being disenfranchised grows daily. And here there is no chance of a "level playing field"! Longer established airlines tend to fix on the need for a mythical level playing field, especially where a new entrant is advantaged for some reason or another and challenges the status quo.

But when it comes to data the playing field will be more like a battlefield, with no holds barred. Not only are the legacy airlines themselves negligent in their failure to exploit their opportunities, they are distinctly at a disadvantage as against other, newer forms of information collection and exploitation.

Aggregators of data, whether they are travel related such as OTAs, or social media such as Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple or any of a number of major (yet-to-exist) organisations likely to appear over the next few years, already have far better data on most of the airlines' customers than the airlines do themselves.

As favoured targets of government oversight, the airlines are always in the spotlight when it comes to privacy rules and storage and use of data about their customers. Constant attacks on airlines' cross-border data transfers, commercial and even security-related, constrain their

every move.

In stark contrast with the strict framework controlling the airline business, the internet has encouraged a form of global data quasi-anarchy.

Here, the new data miners have a great advantage. At the front of a new wave, they are able to be much more cavalier about conformity with old norms - even when they are technically limited by them.

In stark contrast with the strict framework controlling the airline business, the internet has encouraged a form of global data quasi-anarchy, in which many of the norms of law and legislative process are constantly being challenged. Most obviously, regard for personal privacy principles has fallen victim to the potential to monetise this data.

At the same time the internet and social media are also reformulating many of our ideas of democratic participation. Events such as WikiLeaks will not be one-offs. Already their emergence has defied established information norms and shifted legal philosophical grass roots thinking about data access.

Does the market like data?

Market capitalisation of some leading IT companies

The old norms remain, but the nature of the challenges to the status quo is changing. Traditional forms of law have not yet been able to cope with the implications of multi-jurisdictional data gathering activity in social media fora. So, where one jurisdiction acts to slow or suppress activity under its national legislation, global pressure immediately emerges to try to prevent restrictions leaking into other markets.

The sheer weight of participation in this global democratisation of information flows guarantees its revolutionary impact. It is not an even transformation, but constantly in flux, unpredictable but moving relentlessly in one direction.

This global data power tends to lead to a shoot first-litigate later modality, constantly pushing the boundaries of what is possible. Airlines however are hemmed in by often-specifically airline-targeted cross-border data transfer limitations; they must go to enormous lengths to comply, always at risk of expensive compound legal actions and penalties.

The new miners can do this because they are big, powerful and growing. They could not be further from the Rust Belt. And the market reflects it. These companies are influential and they understand data.

And despite their best efforts at compliance, the relatively tiny airlines are frequently in technical breach of privacy legislation in multiple jurisdictions. This springs at least partly from their effective outsourcing of recording of PNRs to GDSs. In other words, ironically, the airlines are as a result often in breach of data gathering laws even though they can't access that data effectively themselves!

For airlines, transforming a business model from reliance on flying aeroplanes to actually maximising revenue potential requires a major reversal of decades of same-old-same-old thinking. For a CEO to present to his or her board a proposal that relegates the flying operations from centre stage to a supplementary role would today be regarded as close to heresy. Most airline board members come from airline or finance backgrounds and have little comprehension of the opportunities represented by data mining. The majority would regard social media as a fad (which, in its present form, it may be, but it will mutate quickly and constantly).

This will change. Indeed the thinking that emerges from a successful FFP can permeate management thinking when it delivers profits wildly in excess of the airline operations. There is already a spreading recognition of this. For more and more legacy airlines, it is patently clear that the sum of their parts is worth more than the whole - in some cases dramatically so. The poor performer among the groups is the airline activity. This a hardly a new or controversial phenomenon.

Private equity investor Robert Milton decided to apply this thinking to his then airline, the very legacy Air Canada, almost a decade ago. From a bankrupt airline (then undergoing a form of Chapter 11 creditor protection) he stripped out the FFP and formulated it as a whole new investment entity. The airline was also divested of its profitable engineering services and new lower-cost airline brands were folded in.

Today that FFP has become the profoundly successful Aimia, formerly Groupe Aeroplan. Aimia is now valued at over USD2.25 billion, very close to 10 times that of the still very-legacy Air Canada. It has become a model for loyalty programmes. However, despite its government's highly protectionist policy regime designed to support Air Canada's international services, the airline is once again teetering on the edge of bankruptcy as its powerful unions challenge management attempts to find a way out of near-insoluble difficulties.

Mr Milton is no fan of airline unions, a sentiment that is warmly reciprocated. As he says in his book, Straight from the Top: The Truth about Air Canada, "... the leverage of airline unions is near-absolute, leading to one-sided agreements that are the basis for many of the crises facing the legacy airlines. In essence, airlines like Air Canada are operating with deregulated revenues and pre-deregulation labour relationships, a recipe for financial disaster unless they are by some means injected with a dose of reality."

By exposing the legacy airline elements of the entity, Mr Milton has provided a powerful example of the way components of the airline group can be value-maximised. (Not all of the subsequent history has been good news though for those entities. After on-selling the maintenance activity to another private equity group, that company was recently bankrupted, causing considerable commercial and political fallout.) More importantly he has also illustrated that the residue, the core of legacy airline operation, is severely impaired. And there is no evidence to suggest that situation is about to change.

But that is only one side of the emerging prospect of data use and disenfranchisement. In this scenario, it is airline managements too who are embedded in classic legacy operational mindsets.

Click here to view a cutting edge html5 version.